by Charles Hartley

First published in The Pioneer News on 25 May 2020

For those of you looking for my monthly "It Happened in Bullitt County" article, we have been unable to access the necessary microfilms at the public library due to the pandemic, so we are presenting this instead. The "Happened" articles will resume as soon as we are able to continue our research. Parts of the following were first published in a Bullitt Memories article in 2014.

With the COVID-19 pandemic on our minds, let's take a look at another pandemic that began over a hundred years ago.

The influenza virus, now labeled influenza type A subtype H1N1, first appeared in Europe in March 1918, during World War I. The first wave quickly spread across the continent. It was comparatively mild, but a second wave developed in August that was more lethal. To maintain morale, wartime censors held back early reports of its effects in Germany, Britain, France, and the United States, but newspapers could report on its effects in neutral Spain, leaving the impression that Spain was especially hard hit. Thus it became known as the Spanish flu pandemic.

When the flu began appearing in Louisville, the city had about a thousand cases during late September. By the third week of the epidemic, Louisville was experiencing about 180 deaths a week from influenza. Soldiers at Camp Taylor were hit harder than the city itself with soaring infections.

The outbreak quickly spread from the larger cities to smaller communities, and over a six month period beginning in October 1918, it killed 68 people within Bullitt County. An analysis of these 68 people shows that about a third of them were under the age of 10, while another third were between the ages of 20 and 40. This was typical of the pattern around the world. To a lesser degree, it also included the elderly.

As it is now with the COVID-19 pandemic, there was no vaccine to protect against infection. To make matters worse, there were no antibiotics to treat bacterial infections and the pneumonia associated with the infection.

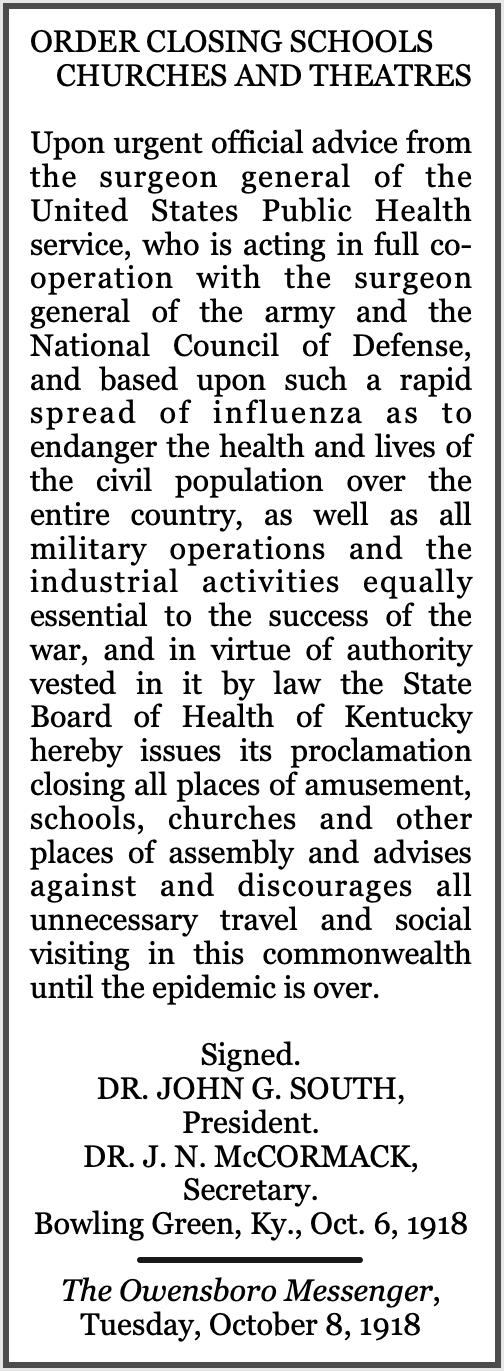

On October 6, the State Board of Health of Kentucky issued the proclamation shown here.

Then, as now, the only available control efforts were limited to interventions such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limitations on public gatherings. Such measures were limited in their effectiveness by how willing people were to follow these steps, as is the case today.

We can't begin to describe the heartache that swept community after community, but a few examples from Bullitt County may serve to help us understand it.

On October 13, Ida Mae Harris, who lived near Gap-in-Knob, was the first to die in the county, She was 26, daughter of George and Mollie Jackson, and wife of Tom Harris. Besides them, she left behind a four-year-old son.

The next day John William Ford, a railroad engineer, died at Lebanon Junction. And the day after, his wife Abigail Ford joined him. John was 44, Abbie was 31.

That same day, little Oleta Armstrong, seven-year-old daughter of Walter and Lida (Croan) Armstrong, succumbed to the virus.

The Pioneer-News reported on October 25, 1918, "The Spanish Influenza which has been spreading all over the United States and other countries and killing thousands of people, claimed several victims in Bullitt in the last three weeks, causing the death of several of our most prominent people, as well as many of the younger set. At one time, eight corpses were lying in the quiet little town of Lebanon Junction."

John Langley, like so many of his Lebanon Junction neighbors, worked for the railroad. He and his wife Lilly had nine children, but two of their youngest were snatched away by influenza, first Gilbert on Oct 16, and then Harland two days later. Gilbert was seven, Harland six.

Henry Priddy's sons, Abner and Robert, were working at Camp Knox when they were stricken with influenza. They returned home in the Hebron community and their whole family became infected. Abner died on Oct 28, 1918; his brother Robert followed two days later, and their father died the next day. It was thought that Mrs. Priddy and the four remaining daughters would survive, but the baby, Lilly May succumbed three weeks later.

By the end of October, thirty deaths in Bullitt County had been attributed to the virus or its complications. November would see ten more, and December would add a dozen more.

The coming winter and spring would see a third wave of the virus bring additional deaths.

Everett and Blanche Armstrong of the Pleasant Grove community were a young couple with three small children when influenza swept through their home. Blanche died of pneumonia on Dec 9 and Everett followed two days later, leaving behind three small orphans.

Susie Lillian (Murphy) Bowman left behind her husband Howard, and their infant baby boy Charlie, when she died in December at the age of only 26.

The death toll would continue to mount, with families in all parts of the county suffering loss.

Whitson Dillander, whose family lived on Ridge Road, succumbed on December 5, leaving behind his parents, and his wife Mary, along with a son and three daughters. Mary was carrying his fourth daughter who would be born in April.

When John Richard Ferguson, a farmer at Brooks, registered for the draft in September 1918, he listed "three children" as his nearest relatives. Less than four months later John was crushed by the loss of those children. On Thursday, January 9 his 14-year-old son Earl died of pneumonia. Then the following Sunday both Hazel (11) and Viola Mae (5) lost their battle with influenza.

Edward and Edith (Scott) Owen lost their three-month-old son Marion on February 24, and John and Lizie (O'Connell) Atcher lost little John Christian Atcher the next day. He was one.

The toll of infant deaths continued with John and Sybl (Perkins) Tinnell's daughter Dorothy; Clay and Sallie (Hood) Brown's son Wallace; and Robert and Mabel (Harris) McAfee's son Gerald, all in March.

There would be others, but the count was beginning to slow, and by summertime the virus had largely disappeared.

Most deaths, both here and around the country, occurred during that horrible second wave. One estimate puts the death toll in the United States at over a half million people. I've read further estimates of a worldwide death toll of fifty million lives.

Then, as now, folks grew weary of being frightened, and being denied the normal lives they longed for. Outbreaks of the virus continued into the 1920s, and variations of it have continued to rear their ugly heads right up to the present.

The influenza virus sometimes seems to lull us into complacency with milder versions, but make no mistake, the form that killed thousands of Kentuckians in 1918-1920 is still alive and capable of returning with a vengeance. Today we have better methods of dealing with these viruses, but only if we use them.

And now we again must deal with a virus for which we presently have no cure or vaccine. The steps thus far taken to deal with it have not pleased all of us; but, if we do not stay the course, we risk having this pandemic grow worse.

In writing this, I was reminded of an unrelated story that, in at least one sense, speaks to where we stand today.

In the 1830s, a turnpike was built between Louisville and Bardstown which passed through Mt. Washington. The law creating it required mile posts to be placed along it, much like the mile posts along our highways today. One of those old mile stones still stands today in Mt. Washington. Some may recall that a group of Mt. Washington high school students recently restored it and the historical marker standing beside it.

But here's the thing, that stone is engraved with the letters and numbers 20 L and 19 B, indicating that the traveler from Louisville had completed just over half his journey to Bardstown.

Before reaching that milestone, he had to follow the terrain down to Floyds Fork, and then climb the hill into Mt. Washington, no simple task for a man on foot or horseback. But by reaching this milestone he knew that his journey was a bit more than half concluded. He still had a way to go, including more up and down terrain, but part of the journey was behind him.

I think that is where we are today with this pandemic. We've already passed through a hard part, and likely still have some difficult terrain ahead, but like our traveler, we just need to keep putting one foot in front of the other until we reach our destination.

If you, the reader, have an interest in any particular part of our county history, and wish to contribute to this effort, use the form on our Contact Us page to send us your comments about this, or any Bullitt County History page. We welcome your comments and suggestions. If you feel that we have misspoken at any point, please feel free to point this out to us.

The Bullitt County History Museum, a service of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is located in the county courthouse at 300 South Buckman Street (Highway 61) in Shepherdsville, Kentucky. The museum, along with its research room, is open 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday. Saturday appointments are available by calling 502-921-0161 during our regular weekday hours. Admission is free. The museum, as part of the Bullitt County Genealogical Society, is a 501(c)3 tax exempt organization and is classified as a 509(a)2 public charity. Contributions and bequests are deductible under section 2055, 2106, or 2522 of the Internal Revenue Code. Page last modified: 12 Jan 2024 . Page URL: bullittcountyhistory.org/bchistory/pandemic.html